Functional programming: Enemy of the state

A quick google search on “Why functional programming” or “why functional programming matters” will yield insightful results. Having that said, there is still more to add to this topic. And what would be my answer to these questions? One word: purity (or Statelessness). Before delving into purity, let’s dissect the function in the functional programming paradigm.

I was baffled when I first heard the term functional programming many years ago. I said, “Hey, I have been using C. We already have functions there, and JavaScript also has functions, as many OOP languages have functions disguised as methods of the objects. So why is this new term?”

My first mistake was that functional programming was a new term. The conceptual origin of functional programming lambda calculus was developed as early as 1930 by Alonzo Church, and the first functional programming language, LISP was available by the late ’50s. So functional programming wasn’t something new at all. My second mistake was the confusion about the term “functional”. The word function here does not represent the procedures that we call functions in the programming languages, but rather it refers to the mathematical functions just like Sine and Cosine. And it is purity that makes these mathematical functions different than the functions in those imperative programming languages. That is, given the same input for a pure function, that function will always yield the same output without any side effects.

For example, sin(90) will always yield 1. As a result, no matter when or how many times you call. Such function calls also have no side effects. That is, pure function calls will not alter anything you care about.

On the contrary, imperative programming languages will not constrain your functions to be pure.

A common argument is associated with the functional programming paradigm, that it mainly applies to mathematics and science or finance, but how about the real-world line of business applications? The line of business applications is precisely where functional programming shines. But before claiming functional programming is the holy grail, let’s review some misconceptions about functional programming.

Misconceptions about functional programming

When we ask developers, what are the characteristics of good code or a good programming language, you would likely hear the following:

- Good code is more maintainable.

- Good code leads to better readability.

- Good code tends to be shorter and concise.

- Good code is testable, and dependencies are isolatable.

- Good code is extendable.

- Good code is less buggy.

Functional programming is not some sort of code, nor is it a language but a paradigm. You could probably go with functional programming by using any language. However, some languages embrace it as a first-class citizen (or even dictate it). In contrast, some languages tend to be challenging or become too verbose to go with functional programming. Thus above items about good code are not really relevant to the functional programming paradigm. I would like to emphasize once more the following:

- Functional programming does not necessarily lead to more maintainable code, nor does it aim for that.

- The code written with functional programming languages is not necessarily more readable.

- The practice of functional programming can also turn the code into spaghetti if one is not careful.

Wow, why should I use it all if functional programming doesn’t give me those aspects I care about in my code?

Why should I care about functional programming?

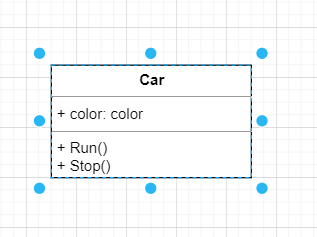

We have discussed functional programming does not necessarily lead to better code. So why bother? Functional programming keeps the developer sane, and you will sleep better! Let’s see how with an example. Suppose we have a Car class with a public property Color and two public methods, Run() and Stop(). The Run method does whatever is internally necessary to run the car.

Now we do the following:

var car = new Car();

car.Run();

... //do other things.

SomeOtherFunction(car);

//Did SomeOtherFunction stop the car? I don't know; I have to track it.

... //other things

SomeOtherFunction(Car car){

//hmm, have I run the car before? I have to track it.

car.Run();

//now I have how to run the car perhaps more than one time. What's going to happen?

}

We have three problems here:

1- As the author of SomeOtherFunction, how will I know if the Run method was called before? I need to look up the caller’s code. Thus, it’s an extra burden for the developer to find it out. One might argue, we could add an IsRunning property. However, nothing forces me to compile time to check that, and I could easily forget to do such a check. And not always such properties and methods related. So I am burdened with reviewing the caller’s code. Worse, if SomeOtherFunction is a public surface for my API, I have to be extra careful. I have to resort to defensive programming, document my API, clearly describe the expected input state, and pray for the caller to read the docs.

2- What happens if I call Run twice? Will it throw an exception? Will it ignore? The only way to find out is to read the relevant API for the Car class or the source. Hence we have another burden here.

3- After SomeOtherFunction returns, how do I know if the car is stopped or not? Again we have to read the docs or the source for the SomeOtherFunction, and yet another burden here.

So you can observe such a simple code brings a lot of responsibility to the developer that he has to track and remember the state at various stages of the coding process. It could be easy to remember one object, but having many objects circulating deep into the code may drive you nuts.

How do we solve this problem? Well, the problem is about state tracking, and if we didn’t have the state in the first place, we wouldn’t have that problem.

The functional solution

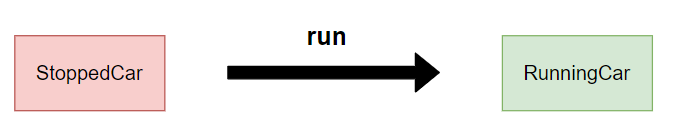

So we want to get rid of the state. Perhaps a way to do so is to represent the state using the types. So instead of a single Car type, we could utilize two different types: StoppedCar and a RunningCar. Then we have a run function that is taking a StoppedCar and returning a RunningCar:

Once we define such a run function, we solve all three problems. First, we always know that if the car is running:

SomeOtherFunction(RunningCar car){

//we know for sure the car is running

//you cannot call run again since the code won't compile

}

And obviously, we cannot call the run function again since the code won’t compile. And depending on the return type the caller will know what state has been returned. Now, as developers, we have fewer things to track and fewer things to worry about. Now life is so easy! Or is it?

If functional programming is so good, why is it not popular?

Well, the first thing to acknowledge is functional programming is not about syntax. It’s a paradigm. For example, recently, C# 9 has attained the record syntax, a record is a functional concept, and if you are unfamiliar with the functional paradigm, you might be confused about why we need records in the first place. You will only see unconvincing answers like records are good because they are immutable (the real answer is they provide value semantics and referential transparency. Thus, we don’t care about the memory location, whereas immutability is only a vehicle to achieve these).

I am trying to say that to start functional programming, you have to forget most things you already know about imperative programming. So it is baby steps again, and it would take quite a while to master it. And that is one of the significant reasons people shy away from functional programming.

In the imperative world, we have statements that tell the compiler what to do:

- do this;

- do that;

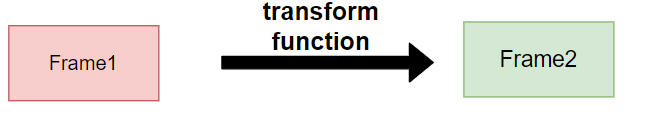

Whereas functional programming is more like movie frames. Each frame is immutable and unchangeable, but if we roll 24 frames per second, it creates the illusion of a movie.

Functional programming does the same. We never change the data, but every time we need a change things, we create a new instance of that type. And obviously, that’s a lot of CPU cycles and memory allocation compared to the imperative approach, and 30 years ago, that really mattered. Thirty years ago, your colleagues would say, “Whoa! Are you allocating 200 bytes just to change the status of a car?” But these days, it is engineers are expensive, and servers are not. Now, your users are unlikely to notice a few hundred nanoseconds delay. But you could utilize the hardware power for the sake of programmer productivity. Thanks to immutability, functional paradigm even scales better when you have a distributed and/or multi-threaded environment. But these historical problems regarding the resource consumption associated with functional programming allowed the imperative paradigm to flourish, whereas people remained skeptical of functional programming.

Having a smaller community leads to fewer examples, fewer resources, and less tooling. You can find many articles and books about functional programming, but try to find a functional sample application for something like a simple to-do list that persists the data to the database. You will be mostly out of luck, and you might fall back trying to use old tools like ORMs. But then you will be frustrated and ask yourself why to bother with the functional way. Indeed, CQRS with event sourcing is one of the correct ways to persist the data in functional programming instead of ORMS. Aaaand you have another thing to learn!

Combined with the relearning process described, functional programmers are a minority in the developer community. Today’s challenges require complicated solutions, and solutions like reactive programming are becoming increasingly popular. One of the most famous and demanded javascript libraries is React. React is an excellent example of demonstrating how functional and reactive programming shines. Single-page applications are way more stateful than the backend counterparts since, usually, the backend only serves the data by relaying in and out from the database without holding up the state. Today many developers have appreciated how React (and redux-like solutions) helped them to scale their complicated applications. On the infrastructural side, we are increasingly interested in declarative solutions.

We are at the edge of madness concerning OOP and imperative programming and cannot go any longer. Functional programming is the answer but will the developers throw away their skills and start the relearning process? Who knows.

As of today, lack of resources and tooling, the cost of relearning, unfamiliarity, and other historical reasons pose challenges to flourishing the functional programming paradigm but sit tight. The future might be different.