DDD with Akka Actors

Let’s say you are writing a to-do list application, where users of a company would create tasks where each task has a title and a description. One of the requirements for your application is that the task titles should be unique among all the tasks created regardless of who created them. Also, let’s assume the application is being used by a very large company and there is a lot of concurrent traffic going on.

How would you design your app to fulfill such a constraint? Before reading on I would like you to think about it for a moment.

If you store the data within an ACID-compliant database, you could add a unique constraint to the title column. But aren’t you feeling uncomfortable that we have to rely on an infrastructural entity like a database to fulfill our business need?

Perhaps it is the best solution you can get with the CRUD mentality. The very problem is actually the source of truth, being the database as if the entire application behaves like a dummy mock just to satisfy the database itself, the development becomes database driven. Can we move the source of truth from the database to our application?

In order to move the source of truth to our code perhaps, you would suggest using ORMS. But then I’d say, Objects in OOP won’t help you either. Because what we call an object is just a data structure living on a pile of allocated memory along with a virtual method table for its methods. Such objects are fixed and bound to some physical memory location. Indeed, the objects in OOP are quite low-level constructs and are not good candidates to represent rich domain entities. And we developers deceive ourselves by using ORMs, hydrating the objects, and throwing them out when the request is done. When you have multiple requests targeting the same entities you end up with multiple instances of the same entity and rely on overriding their equality to trick the runtime. The only unique data is within the database rows. I don’t know you, but I feel like it’s just not the real thing. Those objects we hydrate are not truly “alive”. What I would like to have instead “objects” that are alive.

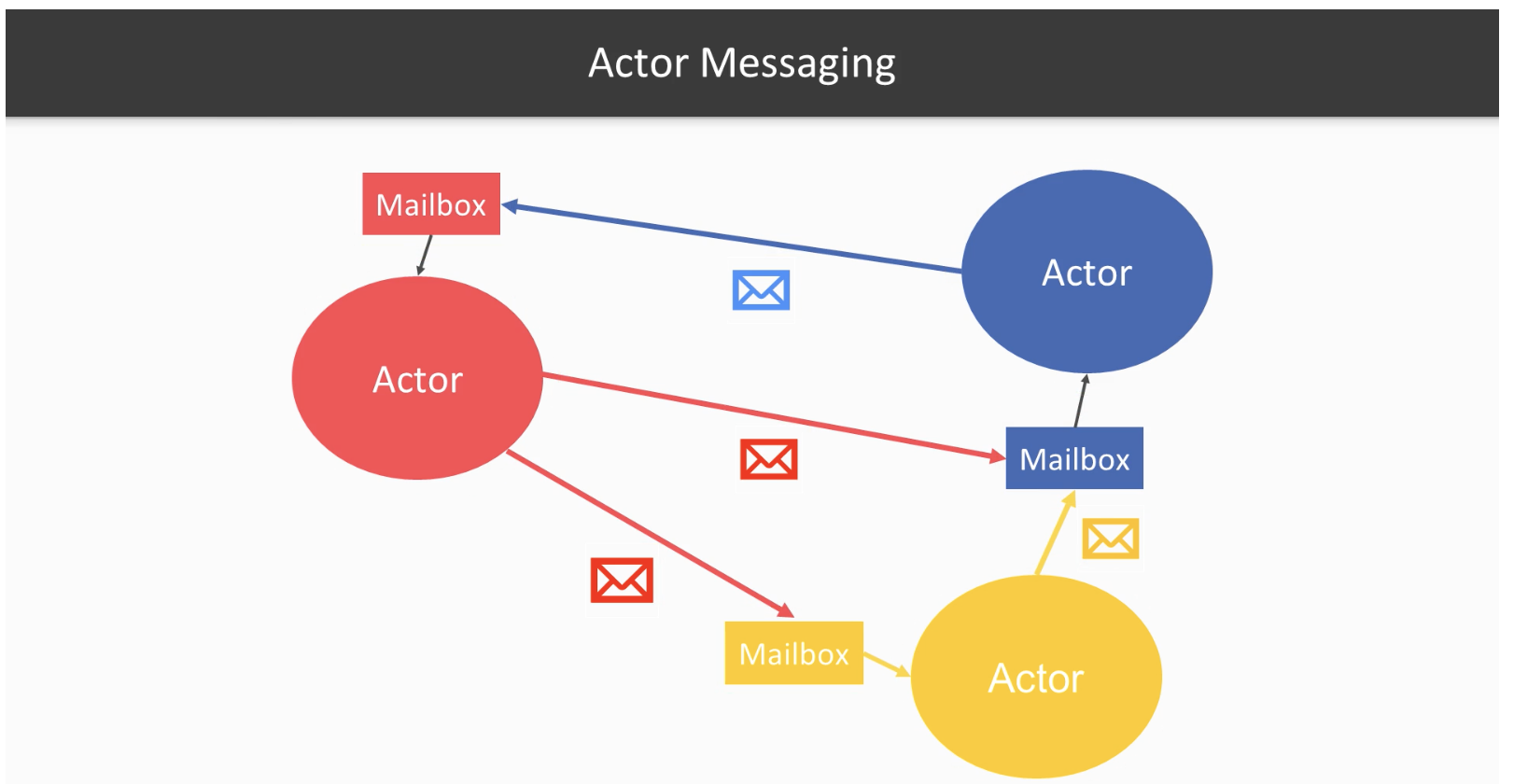

That’s where the actors come into play. By definition, an object in OOP is something that encapsulates state and behavior. Objects expose their behaviors via their methods. Similarly, actors also encapsulate state and behavior. But rather than using methods, you send messages to them to invoke their behaviors.

And unlike regular objects, they are not really bound to some memory location (excluding the illusion created by garbage collectors moving objects around). Indeed, virtual actors in Orleans or entities in Akka cluster sharding make the actors be transparent through the entire cluster such that they are not even bound to a physical machine anymore. When you use such an actor, you really don’t care where the “object” is physically located. Actors also offer built-in thread-safety for your entities. So in other words, actors are better objects to model the aggregates than the traditional objects in OOP. If you could grasp this much, I think you are already enlightened and the rest is just technical details.

You can still use the traditional Objects, but they are meant to live inside our aggregate actors as an implementation detail.

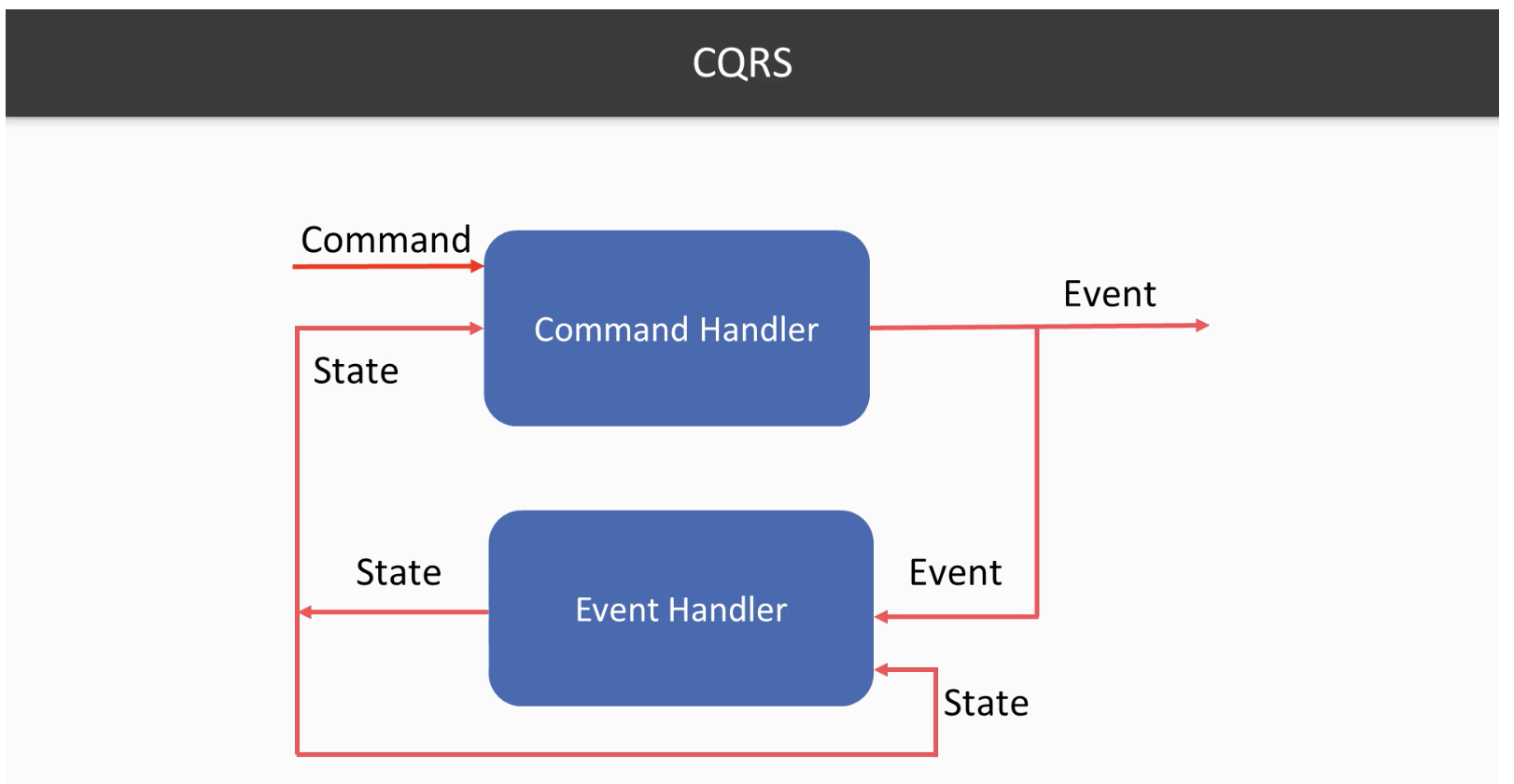

Since we have opt-in for actors, we are to use messages to communicate with them. We could categorize our messages into two. Commands and events. A Command representing a request, a demand, which should be validated. And an event is representing what happened. So Command + Actor’s Old state => Event + Actor’s new State formula applies.

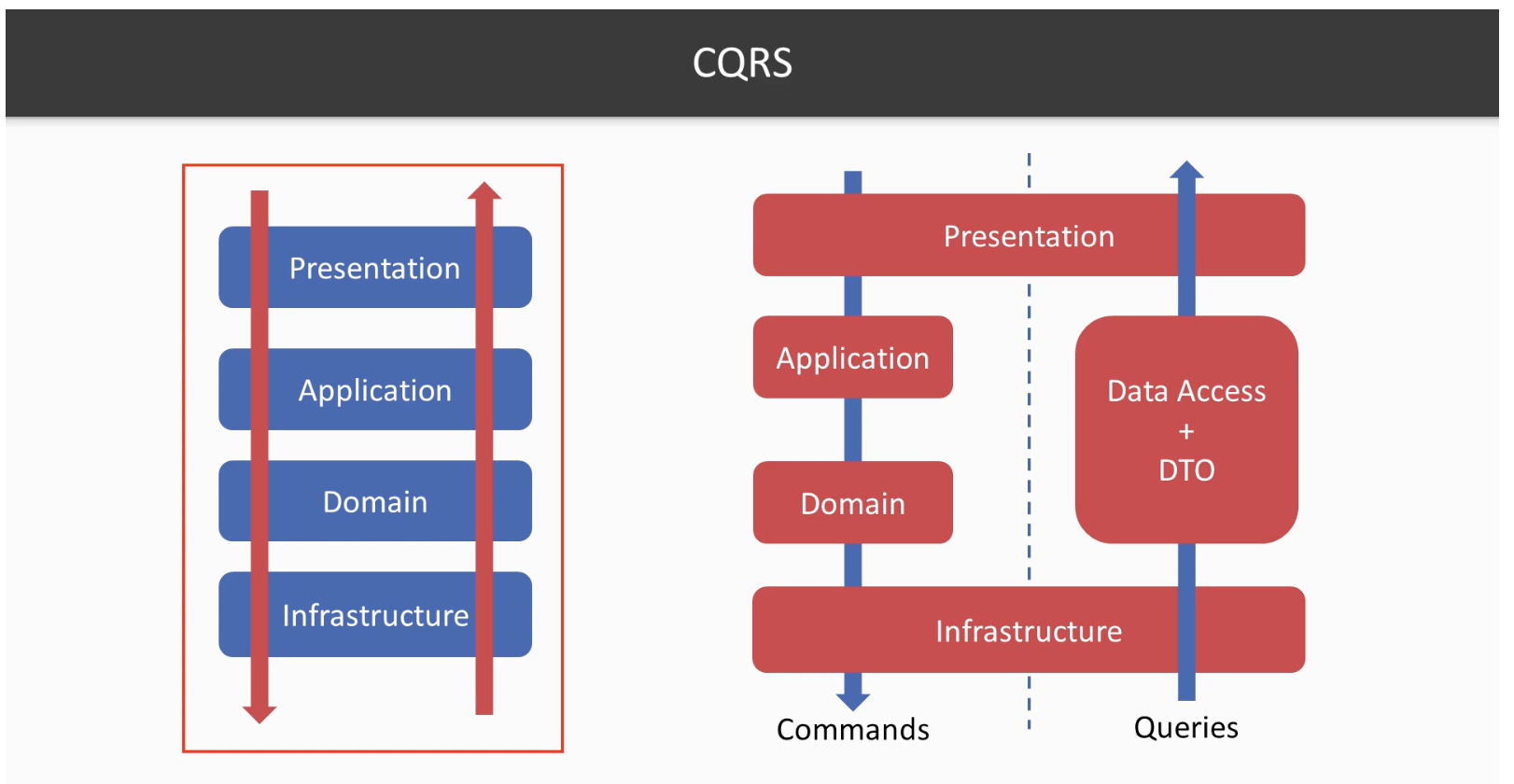

Now why do we use CQRS?

One of the primary reasons to use CQRS is to evolve the query side and command side independently. When you develop your application with a CRUD mentality you don’t know what reports will be needed in advance. In some way, you have to be a fortune teller. You probably have felt that dilemma… Sometimes we use to think like “Hmm which columns should I add to my table to satisfy future reports?”. And while you are trying to play this guessing game, one day your boss asks, if you could give him or her the number of users who had created a task then deleted it within 5 minutes. If you have not added the relevant columns to your store associated with the deletion of a task along with their time stamps, you may not be able to present this report. In other cases, you have the data but you might have to go with crazy scenarios like 4+ table joins.

Worse than that, in CRUD, when you start adding/changing columns, then those changes need to propagate back all the way to your domain, and such changes mean more code changes in the core logic, new deployments, and potentially new bugs and new headaches.

As stated, the primary motivation of CQRS is to segregate your command and query sides such that the implementation of these incoming new report requests will not break anything on the core command part.

With CQRS, you could just add these new columns to the read side without changing a single line of code on the core/command.

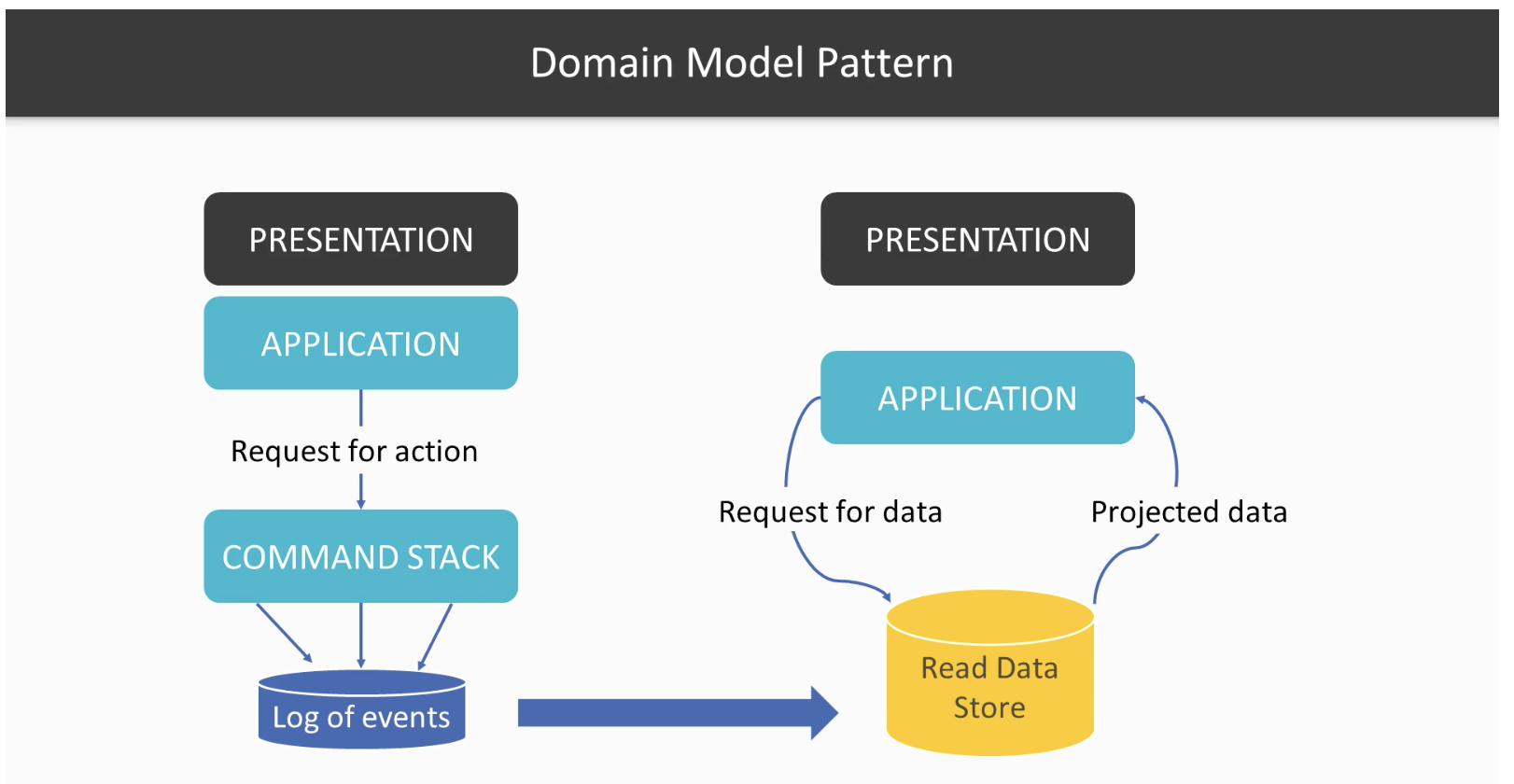

Now you have another challenge though, in order to address all these potential future report queries, you need to record everything that has happened in the system. You could no longer afford to lose a single bit of info/happening in your system. And that’s precisely where the event sourcing comes into play. Because in the CRUD case, if you delete the associated task record when a customer deletes a task, then that info is gone. And don’t get me started on soft deletes, as it is a terrible option either.

Your only bet is to rely on Event Sourcing in order not to lose any data and more than that Event Sourcing is perfectly aligned with the actor way.

Once we have the events persisted, all we have to do is to create a projection service running in the background. This projection service would scan the events, normalize them into records, and then store these records to whatever database we want.

As a typical implementation, you would have an actor for each task, but also an actor for each title where the key of the title actor could be the hash of the title string. And each task creation managed by a Saga/Process Manager. First, a task creation command is issued to a task entity/actor, then that task actor publishes an event like “TaskCreationRequested” which causes a Saga/PM to start and that Saga sends a command to TaskTitle actor demanding a reservation for the title name and if that reservation is successful, Saga would notify the Task actor to continue by sending another command.

Aggregates and Services receive commands and publish events and Saga/PM listens to events and dispatches commands.

The following sequence happens in the entity/actors when a command is received:

- Validate Command

- Create an Event

- Persist the event

- Apply the event

- Publish the event

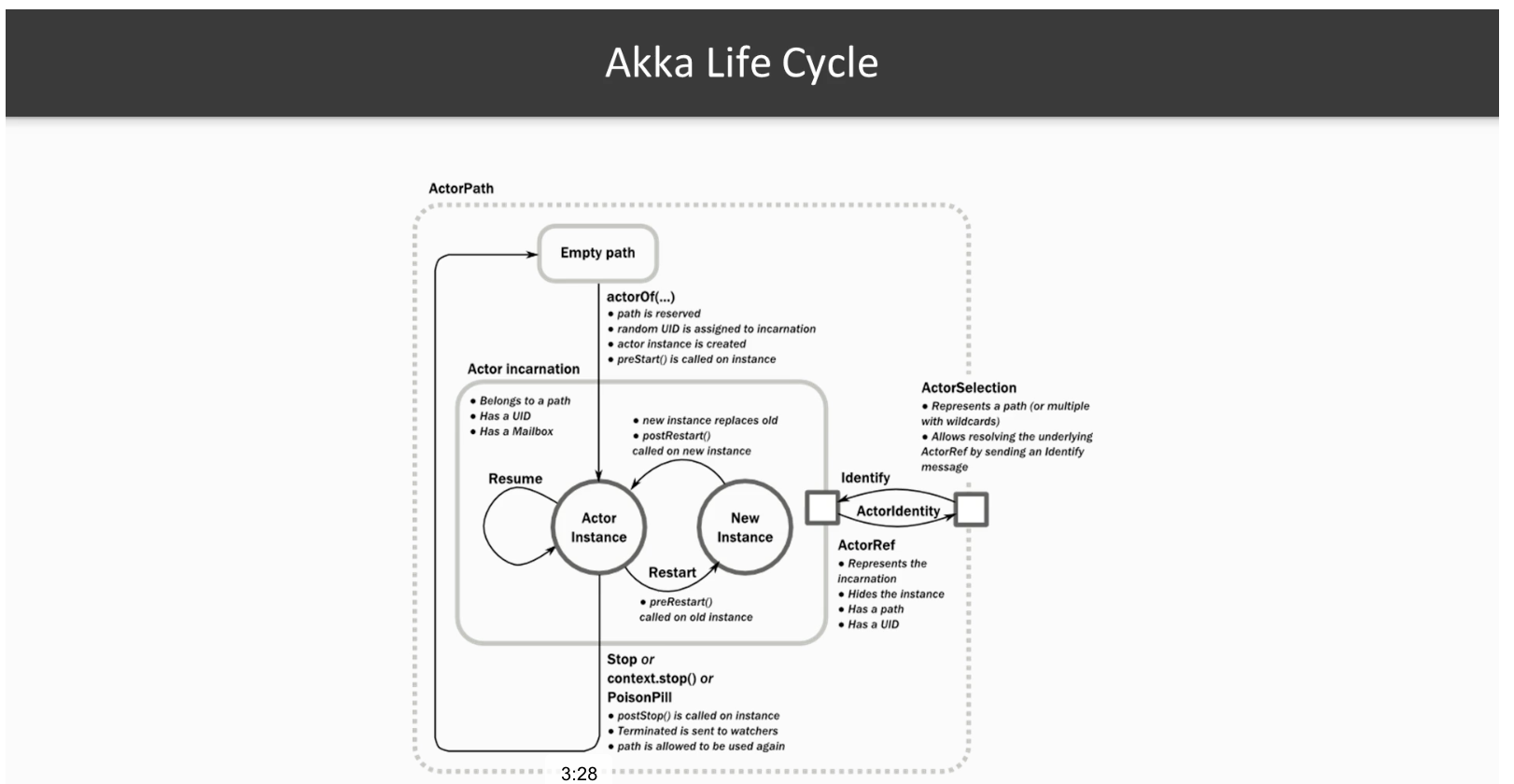

Another important point is we have a concept called virtual actors in Orleans and cluster sharding in Akka and this concept allows us to send a message through an entity id even if that entity/actor doesn’t exist in the first place. And when that happens, the entity/actor will be automatically created for you, without any race condition. As a result, you don’t really care about where that actor is located or created before.

But if we represent all our aggregates as actors, eventually you might end up with thousands of actors and obviously, we can’t keep these in the memory indefinitely. So what do we do?

As for Akka, it offers a setting called passivation. The actor system in Akka tracks the sharded entities and if they don’t receive a message say in 2 minutes for eg. the system gracefully terminates them. However, if those terminated actors receive a message later, then they are initialized again and the state will be replayed and the state will be restored. More than that, the above process is also resilient to potential race conditions.

And as for the process manager, there is another setting called Remember Me in Akka, which would restart those sagas/PMs automatically on a system restart even if the entire cluster crashes thus you don’t have to “remember” which sagas were running before the restart as they would automatically resume.

Finally, you might want to go with a simpler approach as the way described above might be overwhelming and perhaps overly complex for your scenario. That’s certainly fine. In that case, if you would remember our vertical slices concept I have mentioned in the lean development post, you have the freedom to choose different approaches for different layers. The important point is to have your bounded contexts segregated so that in case you have chosen your architectural style wrongly you would be able to drop and reimplement that part without ruining the entire development process.

Afterall, does modeling your domain and services via actors still sound unrealistic? Well, the busiest airport in the world at Dubai disagrees. Entire front services of the border control systems of Dubai Int’l Airport run in Akka actors:

I know, because I designed it :)