CRUD Is Not The Answer: Concurrency

We tend to think typical CRUD applications are relatively simple, however, they have one major important caveat, especially if they are web applications. They involve concurrency! Suppose that we have a banking application that allows us to transfer some amount of money from one account to another. The API takes two accounts and the amount of money to be transferred.

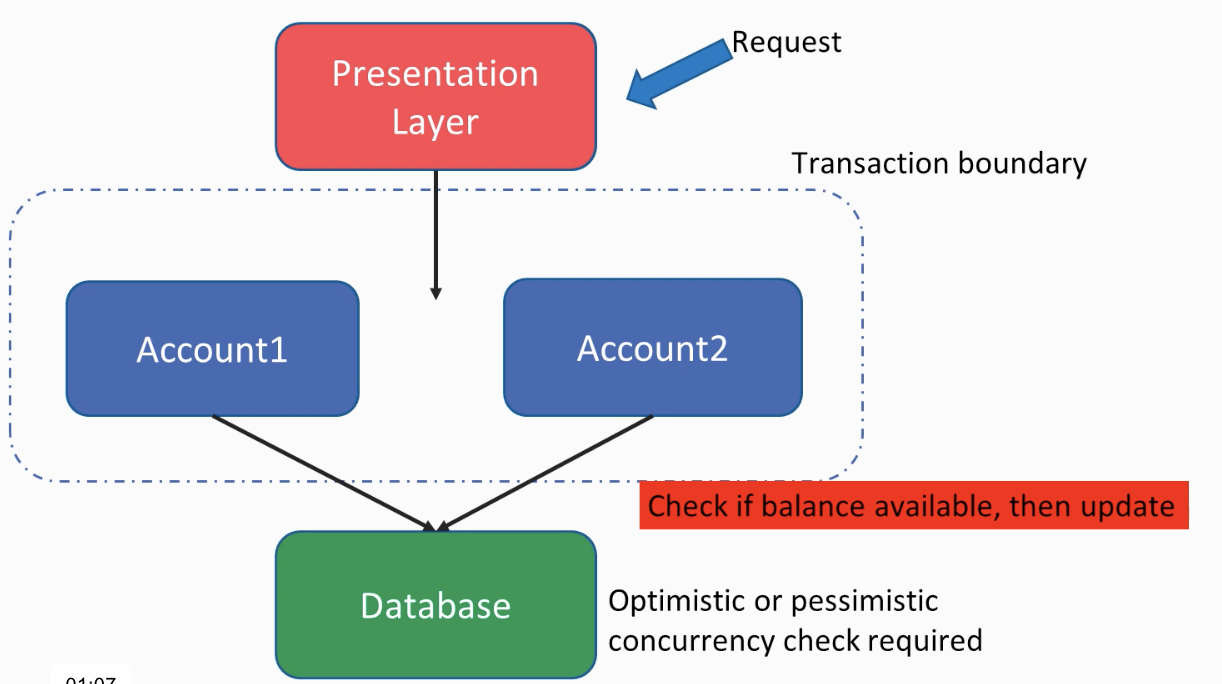

Assuming we use a 3 layered conventional approach, at the top, we have a presentation layer but it could also be some sort of web service interface which receives a transfer request. Once the flow lands to our business layer, we do:

1- Go to the database and check if Acount1 has enough balance, to prevent overdrafts.

2- If it is so, decrement the transferred amount from Account1

3- Add the same amount to Acount2

At this point, we have to identify our transaction boundary. Assuming we have an ACID-compliant database that provides atomicity, we would like these two operations, deducing some amount from Account1 and adding it to the Account2, to happen within a single transaction. Since without the transaction atomicity, if an error happens in between, the database would end up with an inconsistent state.

Having that said, building a transaction boundary like that doesn’t actually solve the concurrency problem. Indeed, it creates the problem itself. As I have just mentioned about ACID compatibility, usually databases offer some sort of isolation between transactions, which stands for the I of ACID.

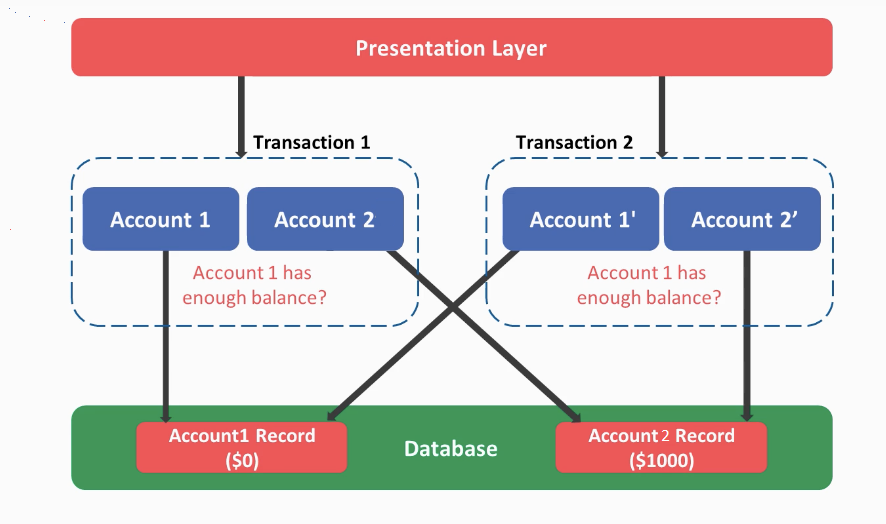

In order to visualize a concurrency scenario, let’s assume there are two requests coming at the same time such that they are both trying to transfer $1000 from Account1 to Account2. During the execution, both transactions will simultaneously check if Account1 has enough balance. Suppose that Account1 has $1000, both transactions will first execute a select query against the data store, and as a result, both will get the result that $1000 is available in Account1 whereas in the actual case only one of these transactions can be successful assuming we don’t allow overdrafts. Subsequently, both of these transactions will reduce $1000 from Account1 and would add $1000 to Account2 accordingly.

Since those transactions are not aware of each other due to ACID isolation, you will end up with Account1 having a $0 balance whereas Account2 would be only added $1000 instead of $2000 and more confusingly, both transactions will succeed. In other words, the net effect of the second transaction will disappear, since both transactions will attempt to set Account1 balance to $0. Our expectation, however, was only one of these transfer requests should be successful and the other should fail due to overdraft.

Generally, such concurrency problems are solved by introducing either an optimistic or a pessimistic concurrency check.

In the case of a pessimistic concurrency check, you basically acquire some lock on the relevant database rows such that no other transaction can read those rows but rather they would be blocked instead. In the above scenario when the pessimistic lock is applied, the first transaction would acquire a lock on the Account1 row and the second transaction would just wait for that lock to be resolved which happens only after the first transaction commits. Yes, such a pessimistic locking mechanism appears to be solving our problem, however, from a performance point of view, it may not be acceptable because we are essentially making some transactions to wait, and in addition to that, since we have locked some rows, eventually it is likely we will end up with a database deadlock at some point in time.

The other alternative is to use optimistic locking. For optimistic locking, we often use a version or a timestamp column and each update statement, which contains a “where” statement against the version/timestamp, checks the number of affected rows to determine if the where filter really hit the record. In case that record has been changed by another transaction then affected rows would yield 0 and denote a concurrency problem. In that case, we have to restart the transaction and run it from scratch. Optimistic locking also solves our concurrency problem but with two big caveats.

1- If we have a very busy system, retrying the transactions over and over again would create a performance problem.

2- If we have any side-effects during the transaction, such as calling an external service, sending an email, etc, re-running the same transaction would put us into a dilemma as in we are to re-create those side-effects.

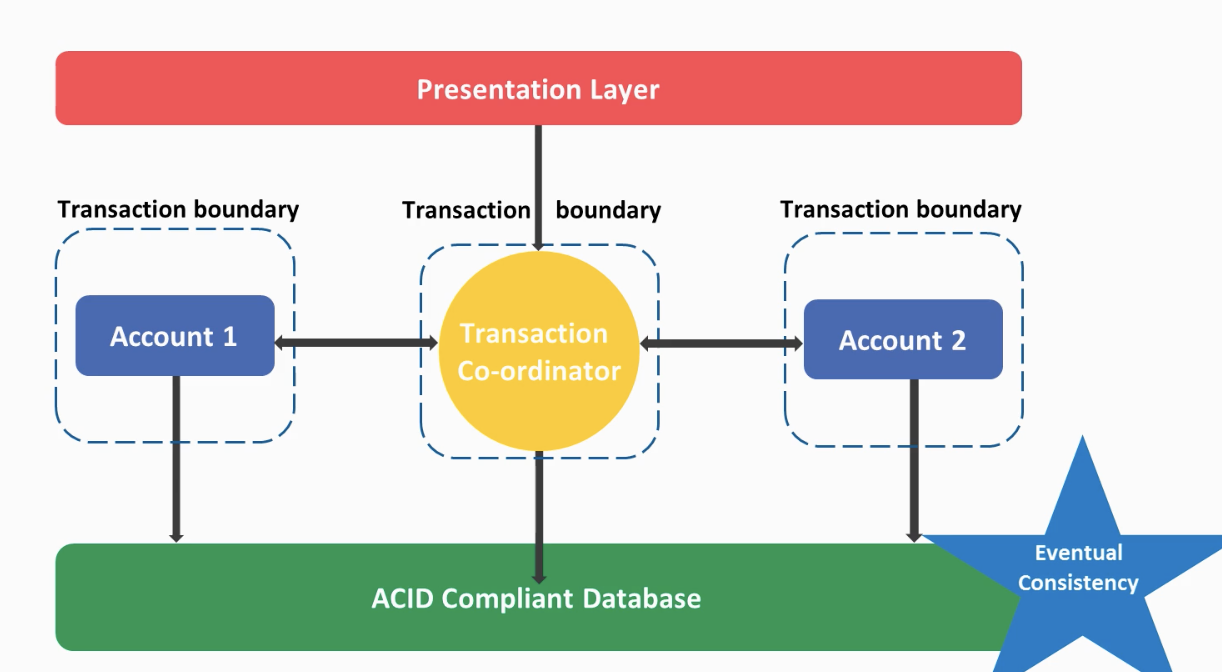

Actually, in proper DDD, Account1 and Account2 would be domain aggregates where each of which should have its own transaction.

But if we use 2 different transactions then we break the atomicity. That is, it would be possible the transaction responsible for updating Account1 is successful but the one associated with Account2 might fail. In order to solve this problem, we could come up with a transaction coordinator that can track the state of each transaction individually. However even if we use such a transaction coordinator, at some point time we could observe, the transaction associated with Account1 has completed, however, the one associated with Account2 is not yet done. The actual consistency will only happen eventually, hence the term eventual consistency is used for such a mechanism. For many developers, the database being in an inconsistent state is somewhat worrisome. However, if you check with other business stakeholders, they may not be worried as much as the developers, indeed chances are high that they might welcome the idea.

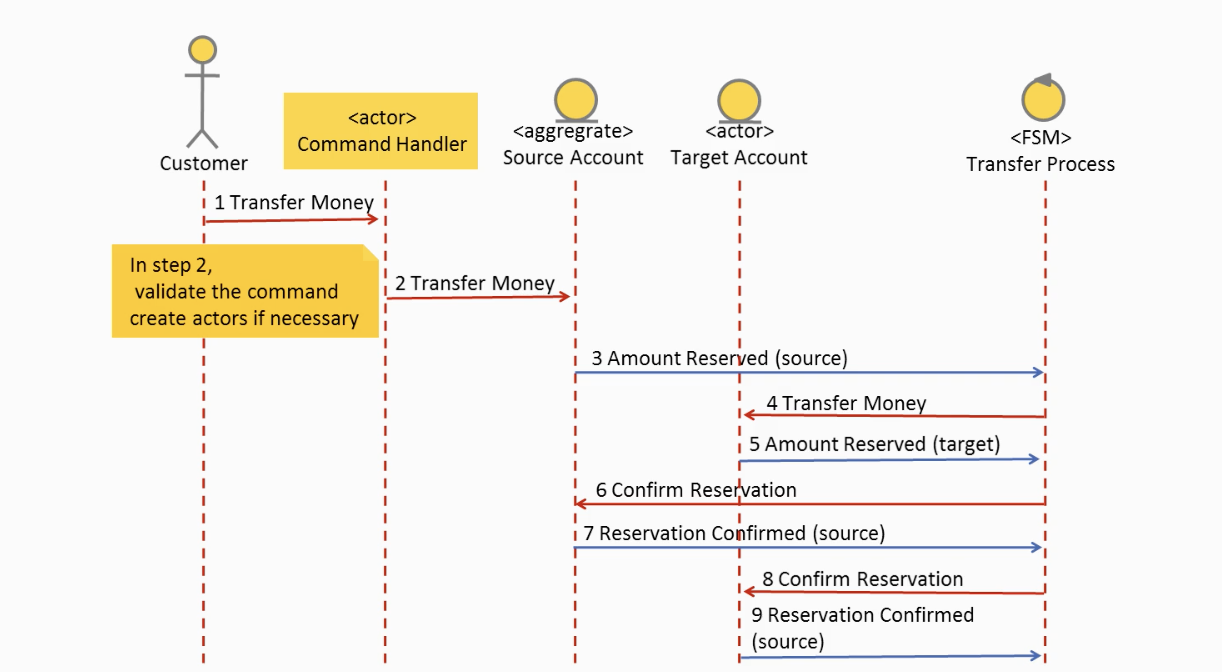

How would the actual sequence diagram look like? Perhaps a simplified version would be as below:

If you follow the numbers you can track the process. The red arrows are denoting the commands whereas the blue ones are the events. A command representing a request, which may be declined, whereas an event represents something that already happened. An aggregate (in this case account) will always accept a command and return/publish an event. Whereas a process or our transaction coordinator will listen to events and dispatch commands to other aggregates/services. In case the system crashes at any point in time when the system restarts the coordinator will recover its last known state, and reissue the necessary commands to resume the process.

Of course from an implementation point of view, this is much more complicated compared to using a single transaction CRUD. There are many CQRS/event sourcing libraries available that could be used. However, in my opinion, Actors are the perfect match for representing aggregates and process managers. In a future post, I will talk about a possible actor implementation of this.

Finally, you may underestimate the danger, perhaps you expect few concurrent users and you’d think concurrency won’t be a problem. Indeed concurrency problems usually are not a major concern among backend devs, however, the fact is, concurrency problems could occur even just by a single user making a double click to a button, in case you forgot to disable the button after the first click or could be intentionally generated for malicious purposes programmatically to break the consistency of database state. For example, let’s say you have built an account lock down mechanism such that account is locked if the user has entered incorrect pin code 5 consequent times, a malicous user may try to burst 10000 request all together and bypass the protection assuming a 4 digit PIN is used.