The tail of a recursion

When I was younger I used to be scared of recursion. Trying to read some recursive funtion was fine, but writing a recursive algorithm from scratch was rather complicated for me as I’d always fall back to the impertive counter-parts. But after sharpening my skills a bit and doing some reading, now I have the opposite impression. Now recursion is rather easy and imperative ones look more difficult. So if you are challenged by the recursive algorithms like me, read on. I might change your idea.

Base case and subproblem

The simple fact it most typical recursive algorithms has two parts. A base case acts like an exit condition and a part that solves only a subpart of the problem. Let’s see an example with a simple sorting algorithm. Please note that our goal is not to write the most efficient code here and the code is rather pseudo:

Step 1: Write the base case

procedure sort(array)

if array.Length = 0

return array

Here we have defined our base case, the exit condition. If the array is empty there is nothing else required we could just return the array itself.

Step2: Assume a solution function already exists but only for a subset of the problem:

procedure sort(array)

if array.Length = 0

return array

first_element, rest = split_first_element(array)

result = sort_already_works(rest)

So we assumed there is already a working sort function called sorting_already_works and we pass the tail part of our array. Since that function is only working for smaller arrays than what we have. Now that the tail is sorted, all we have to do is to insert the first element to the correct location. This is rather easy as you could check the tail until a greater value is found and just insert first_element one before:

procedure sort(array)

if array.Length = 0

return array

first_element, rest = split_first_element(array)

result = sort_already_works(rest)

insert_sorted(first_element,result)

return result

and finally we replace sort_already_works with sort:

procedure sort(array)

if array.Length = 0

return array

first_element, rest = split_first_element(array)

result = sort(rest)

insert_sorted(first_element,result)

return result

Of course, if you want efficiency, you’d better go with some divide and conquer approach and decrease the size of subproblems by some factor. But that’s off-topic for this post.

Let’s look at another example where we would like to find out all permutations of given array:

procedure find_permutations(array)

result = new List()

if array.Length = 0 then

result.Add(array)

result

first_element, rest = split_first_element(array)

result = find_permutations(rest)

You can see we have followed the exact same pattern as before. Here we just accumulate results into a List and the only thing required to insert first_element to every position of all returned lists:

procedure find_permutations(array)

result = new List()

if array.Length = 0 then

result.Add(array)

return result

first_element, rest = split_first_element(array)

result = find_permutations(rest)

for each result_item in result do

for i = 1 to array.Length do

result.Add(insert_at_index(first_element,result_item, i))

return result

It’s easy peasy.

The story of stack and heap

Before diving further, let’s make review our knowledge about stack and heap.

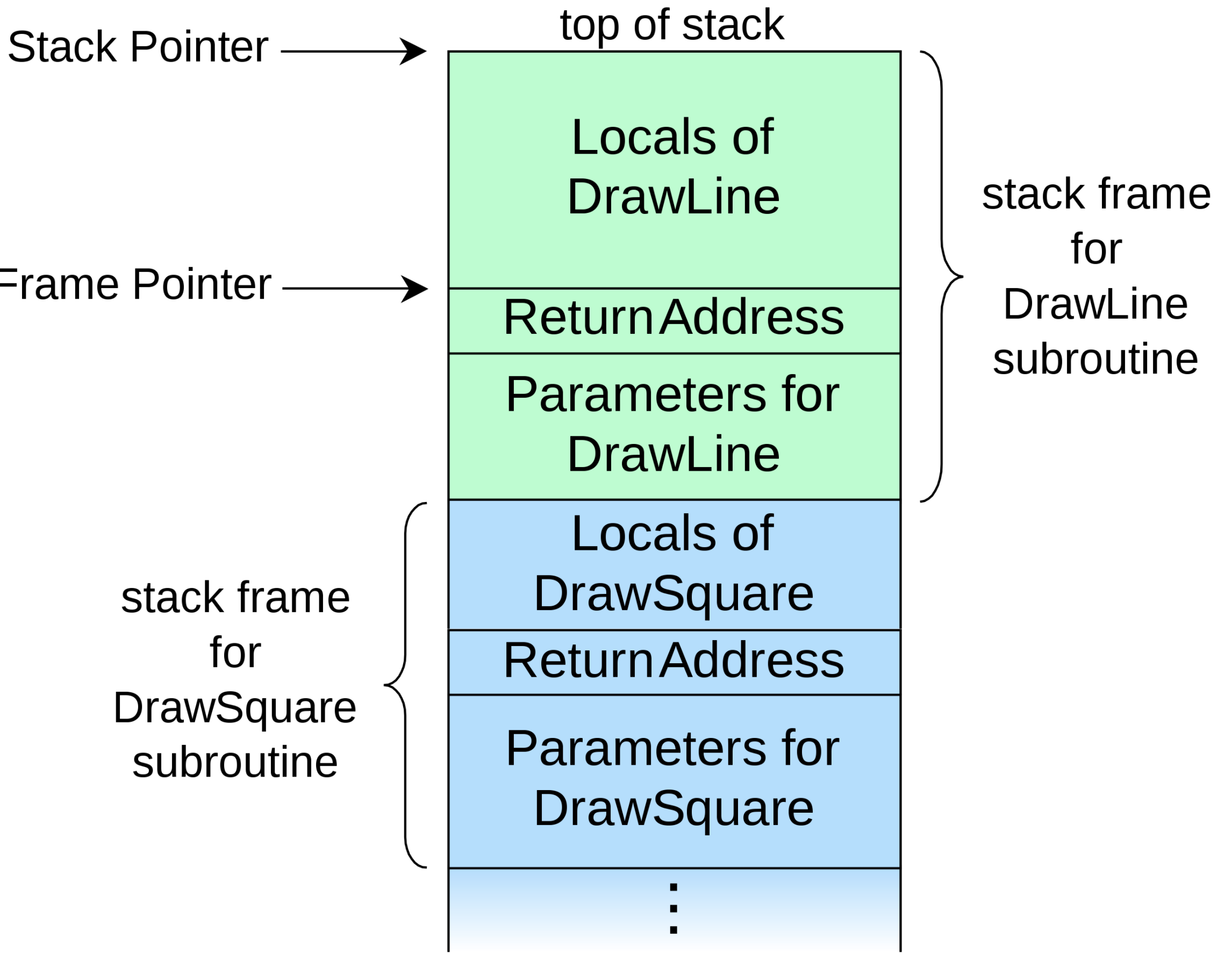

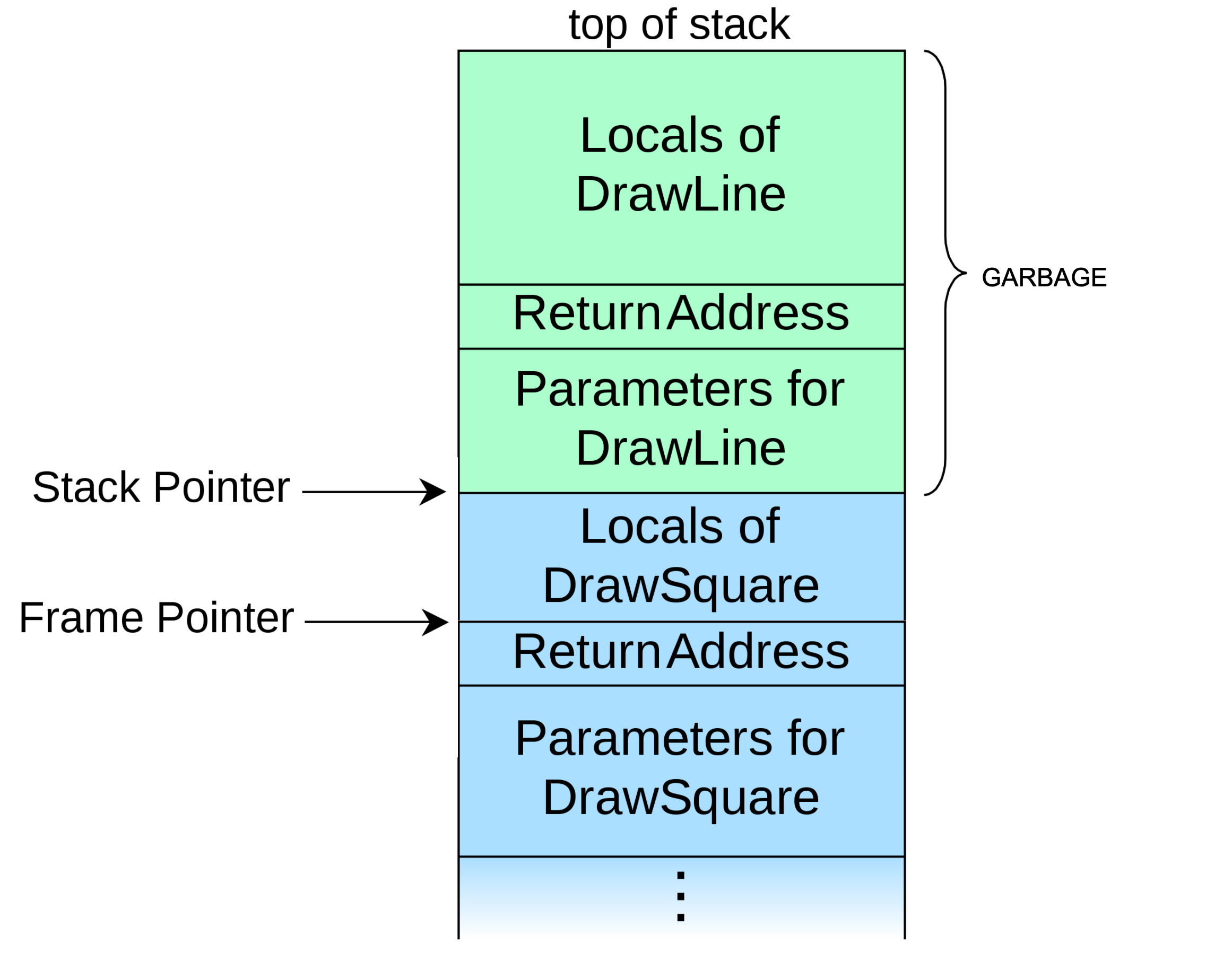

Typically when you start a process, the OS creates some threads for you in order to execute your code. Each thread is given some contiguous memory usually between 1 to 4 MB but that is also configurable. In the stack area, we are allowed to pop and push things. When we push things the stack grows and we pop things, the stack becomes smaller. The end of the stack is bookmarked by a stack pointer in the CPU. If we want to clean the stack, all we have to do is to move the stack pointer to an earlier location and we assume anything beyond the stack pointer is garbage. This way we don’t have to clean the local variables.

Whereas if we want some sort of data to remain even after we return from a function call, stack won’t help us since the stack pointer will rewind and anything that is on the stack after the function returns will be considered as garbage. So for such cases, we use the heap area which is fairly large usually up to Terabytes per process in an x64 system with virtual memory support. Typically we ask the runtime to create a new object and the runtime puts it to some known location in the heap and return us a reference. Then either a Garbage Collector tracks those items in the heap or it becomes our duty to track and remove them when we are done.

Stack of during a call:

When we make a function call, we have to tell some details to the callee, such as the parameters passed and the return address which denotes where the callee should return when it is done. So we have to have a common protocol between the caller and callee. As a convention typically these parameters and return address are put into CPU registers and stack. For example, in x64, the return address has pushed the stack and the first 4 parameters are sent to rcx,rdx,r8, and r9 registers (assuming they are not floating-point) and if we have more than 4 parameters those extra parameters are also pushed to the stack. And depending on the agreement between the caller and callee, either caller and callee clean the stack when the call is done. In general, this is called creating a stack frame.

After the function returns, upper portion of the Stack pointer becomes garbage:

The problems with recursion

So by following 2 simple rules, by specifying a base case and assuming a solution function for the sub-problems exists we can solve most recursive problems. Having that said there a couple of problems with recursion.

1- Every recursive call is a function call: So as we have covered above, there is a lot of ceremony going on at each function call. That means function calls are significantly slower than regular loops, which affects recursive functions in a negative way.

2- The danger of overflowing stack: Unlike heap by default we are only given a few MB stack space. So if your recursive call is too deep, then you might overflow your stack which typically crashes your application. Many operating systems and platforms allow you to define the stack size beforehand but usually, it is not a good idea to mess with these default values unless you really know what you are doing.

The tail of a recursion

So we have seen there are some severe problems with recursion. Yet all hope is not lost. Many compilers are smart enough to figure out your intentions and can provide you some optimizations which are very handy. One of those optimizations is tail call optimization. If you call another function as the last statement before the return and you do not depend on any local variables in the current function then the compiler can skip the above ceremony and make the call as a direct continuation of the current function and can skip creating a stack frame and get-away with a jump statement. If the call is recursive then we have a specialized form of tail call optimization called tail recursion.

More interestingly some functional programming languages like F# don’t have a break keyword to exit from a loop. So it is not possible to exit in the middle of a loop.

let printNthNumber (n:int) =

let rec loop x =

if x < n then

loop (x + 1)

else

printf "%A" x

loop 0

printNthNumber 10

So we are trying to print the Nth number (which is useless I admit) and since we don’t have a break keyword in F#, we decided to use a loop with recursion. Now two questions: 1-) Isn’t this inefficient, just as we are calling another function for every time we loop hence creating a stack frame 2-) Are we in danger of stack overflowing?

Well, apparently the answer is No. If we convert this code to C# by using sharplab.io

We see it is actually compiled to the following code:

while (x < n)

{

int num = n;

x++;

n = num;

}

PrintfFormat<FSharpFunc<int, Unit>, TextWriter, Unit, Unit> format =

new PrintfFormat<FSharpFunc<int, Unit>, TextWriter, Unit, Unit, int>("%A");

PrintfModule.PrintFormatToTextWriter(Console.Out, format).Invoke(x);

So the compiler magically turned out recursion into a while loop hence no stack overflows.

Let’s try C#:

static void printNthNumber (int n) {

void loop (int x) {

if (x < n)

loop (x + 1);

else

System.Console.WriteLine(n);

}

loop(0);

}

printNthNumber(10000000);

Well it is compiled to the below code:

internal static void <<Main>$>g__printNthNumber|0_0(int n)

{

<>c__DisplayClass0_0 <>c__DisplayClass0_ = default(<>c__DisplayClass0_0);

<>c__DisplayClass0_.n = n;

<<Main>$>g__loop|0_1(0, ref <>c__DisplayClass0_);

}

So no tail recursion for C# either. Though I admit there might some cases for JIT is generating tail calls, apparently, this is not the case here.

How about JavaScript?

function printNthNumber (n) {

function loop (x) {

if (x < n)

return loop (x + 1)

else

console.log(x)

}

loop(0);

}

printNthNumber(1000000)

The answer is no for JavaScript, and it fails with Maximum call stack size exceeded

And C++, well C++ is too smart, it eliminates everything and prints the number directly. So to force a loop I also print all numbers

#include<iostream>

int n = 1000000;

void loop (int x) {

if (x < n){

std::cout << n;

loop (x + 1);}

else

std::cout << n;

}

int main()

{

loop(0);

}

And if you call with optimizations you end up with below on Clang:

loop(int):

push rbp

push rbx

push rax

mov ebx, edi

add ebx, -1

.LBB0_1:

mov ebp, dword ptr [rip + n]

mov edi, offset std::cout

mov esi, ebp

call std::basic_ostream<char, std::char_traits<char> >::operator<<(int)

add ebx, 1

cmp ebp, ebx

jg .LBB0_1 # <--- tail recurse

add rsp, 8

pop rbx

pop rbp

ret

Java?

public class HelloWorld{

static int n = 1000000;

static void loop (int x) {

if (x < n){

loop (x + 1);

}

else

System.out.println(n);

}

public static void main(String []args){

loop(0);

}

}

Nope, Java will fail with stack overflow.

Python?

def printNthNumber(n):

def loop(x):

if (x < n):

loop (x + 1)

else:

print(x)

loop(0)

printNthNumber(100000)

Nope, Python also fails with maximum recursion depth exceeded in comparison

Lastly, F# code compiled against Fable and JavaScript also does tail recursion Fable

Well, it is true that tail recursion is a necessity in functional programming languages and perhaps something nice to have on others. And not all recursive functions can be tail-called either. As an example, for typical Fibonacci implementation, fib(n-1) + fib(n-2), will just fail on F# either since this has two recursive calls instead of just one last call.

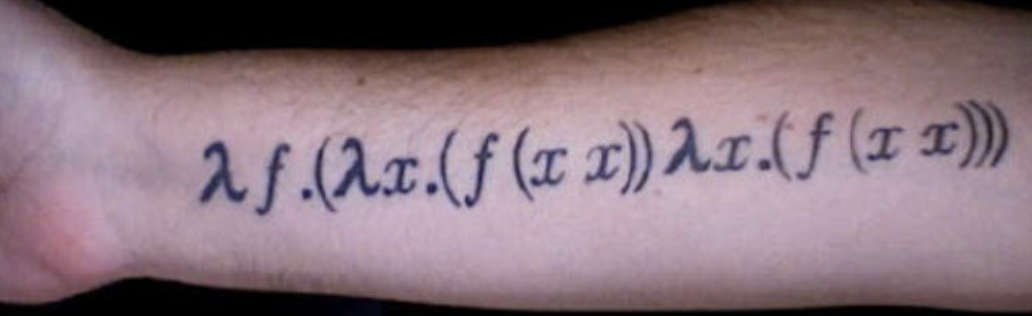

Having that said, I still appreciate this optimization which makes it easier to write some recursive ones. There are other topics like Continuation Passing Style and Y Combinator which I haven’t covered in this post. Let them be a topic for another time.