Does Your Code Pass The Turkey Test? (JS Edition)

The credit for the title goes to Jeff Moser and his excellent post which he authored in 2008. He basically discussed the dangers of improper localization and took a clever approach, stating «“The Turkey Test.” It’s very simple: will your code work properly on a person’s machine in or around the country of Turkey?”». The Turkish alphabet is based on Latin letters but there are few interesting properties of the Turkish alphabet such that Jeff proposes if your code works fine in Turkish culture, then chances are good it is resilient to possible localization problems in other cultures using the Latin alphabet. Perhaps this is a bit overstatement as there are too many different languages and alphabets. However, unless we have a specific focus in a particular language or have dedicated people working on each language, in practice it’s next to impossible to have bug-free localization in our applications. In that aspect, I believe the Turkey test is a low effort way to do basic smoke test on localization for your development process.

In his post, Jeff discusses the localization problems mostly from a .NET point of view. In this post, however, I will try to follow Jeff’s footprints but from a JavaScript point of view.

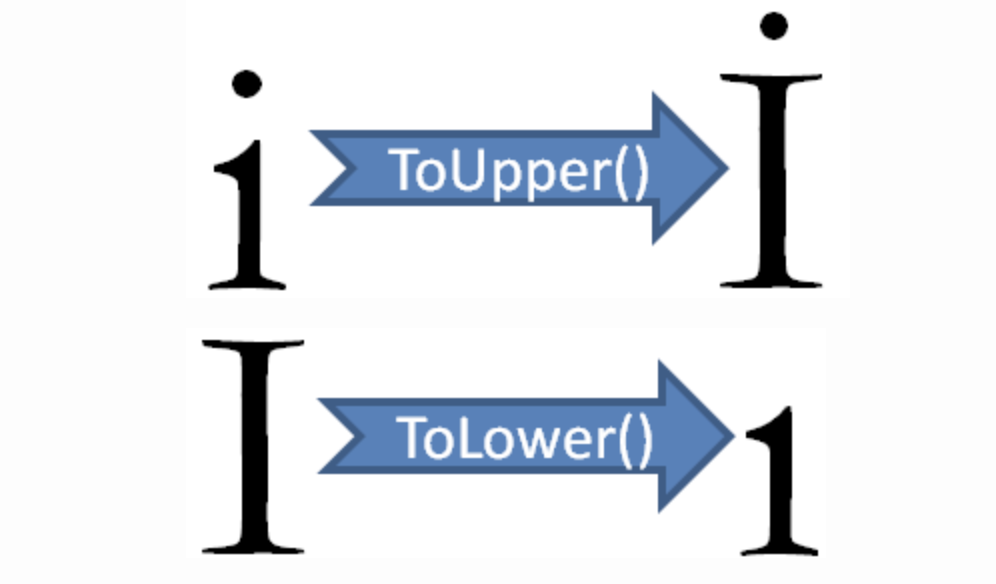

Dotted and dotless I

Well, the obvious question is why “Turkey”? One of the main reasons to use the Turkish alphabet for testing is that that the Turkish alphabet has two “I” letters. One with a dot and one without. Namely the upper case “I” and “İ and lower case “ı” and “i”. And yet there is even a dedicated Wikipedia [article] about it (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dotted_and_dotless_I).

The challenge with these “I”s usually occurs when you try to do a case insensitive equality comparison. As a Turkish, I have been burned very badly because of “I” issues.

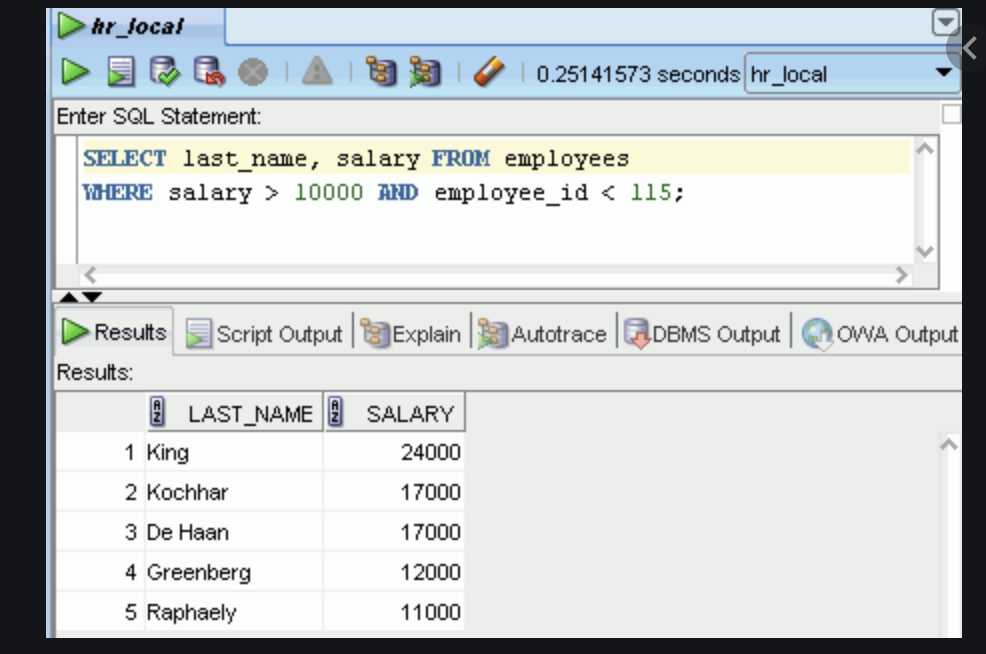

Problems with Oracle (fixed a long time ago)

One particular case I remember is I was developing an application for a bank. We had done extensive testing of the application in the local development environment. But once we deployed the application to the bank’s prod machines, it immediately crashed.

After 13 hours of investigation (at that time my debugging skills wasn’t so sharp so I mostly relied on the logs), I realized my query was in the form of “select description from …” and Oracle database will always capitalize the column names in its results returning a column with “DESCRIPTION”. The developers of ODP.NET were aware of this inconsistency so as a workaround they were calling ToUpper to match the column names from your query. However, if your code runs within Turkish culture then ToUpper call will transform the column name to “DESCRİPTİON” and boom! your code would bail out with a cryptic exception. Luckily only 3 years later Oracle has fixed the issue by using ToUpperInvariant instead of ToUpper

JavaScript world

Having reiterated the problem on .NET, let’s explore the situation with the browsers. The browsers take the current culture from the operating system on macOS and Linux. And on windows depending on the browser they may obey “preferred language” settings. The following one-liner should help you to get the current culture of the browser:

const getLanguage = () => navigator.userLanguage

|| (navigator.languages && navigator.languages.length && navigator.languages[0])

|| navigator.language || navigator.browserLanguage || navigator.systemLanguage || 'en';

Perhaps one of the easiest ways to make case-insensitive but safe comparisons is to use ToLocaleUpperCase and ToLocaleLowerCase:

const city = 'istanbul';

console.log(city.toLocaleUpperCase('en-US'));

// expected output: "ISTANBUL"

console.log(city.toLocaleUpperCase('TR'));

// expected output: "İSTANBUL"

const cityU = 'İSTANBUL';

console.log(cityU.toLocaleLowerCase('en-US'));

// expected output: "i̇stanbul"

console.log(cityU.toLocaleLowerCase('TR'));

// expected output: "istanbul"

Notice the interesting dot on top of the i for lower-case en-us transformation. I have no idea what it is.

JavaScript Internationalization objects

JavaScript also offers several built-in objects for internationalization.

- Intl

- Intl.Collator

- Intl.DateTimeFormat

- Intl.ListFormat

- Intl.NumberFormat

- Intl.PluralRules

- Intl.RelativeTimeFormat

- Intl.Locale

Although I appreciate the effort, I personally find these APIs relatively limited. The internationalization API extends towards interesting problems like pluralization, however, if you review the API, it’s mostly geared towards formatting and displaying but relatively weak when it comes to parsing. First, let’s visit our original problem. Is there another API we could compare “İSTANBUL” with “istanbul” case-insensitively and find them equal?

const a = 'İSTANBUL';

const b = 'istanbul';

console.log(a.localeCompare(b, 'en', { sensitivity: 'base' }));

// expected output: 0

console.log(a.localeCompare(b, 'tr', { sensitivity: 'accent' }));

// expected output: 0

console.log(a.localeCompare(b, 'en', { sensitivity: 'accent' }));

// expected output: 1

It seems to work expectedly. What about the dotless I case? Let’s compare ‘IĞDIR’ and ‘ığdır’ which are considered equal in Turkish case-insensitively.

const a = 'IĞDIR';

const b = 'ığdır';

console.log(a.localeCompare(b, 'en', { sensitivity: 'base' }));

// expected output: -1

console.log(a.localeCompare(b, 'tr', { sensitivity: 'base' }));

// expected output: 0

console.log(a.localeCompare(b, 'tr', { sensitivity: 'accent' }));

// expected output: 0

console.log(a.localeCompare(b, 'en', { sensitivity: 'accent' }));

// expected output: -1

Notice here you must set the culture to ‘tr’ otherwise it won’t work.

Date and Time

Most languages have different formats for dates so if we have 05/01/2021 does it mean January 5th or May 1st?. Some people would argue we should use 2021-05-01 but then your users will complain. How about 01 MAY 2021, this is good but then you have to localize MAY. So pick your poison. To make things more complicated, languages like Turkish use “.” instead of “/” as a date separator.

Furthermore, there is no built-in way to parse such strings to convert JavaScript date objects. You have to rely on external libs like moment.js and there goes another 75 kb to your bundle.

Finally, I should add that, 1 PM is shown as 13.00 in Turkish culture. That’s one more thing you should consider.

Numbers

Well, it’s a well-known fact that different languages use different symbols for thousands and decimals separators. But being uncareful with number localization has dire consequences. In Turkish thousands is split by dot “.” and for the decimal separator “,” is used. For example 1.234,56 is one thousand two hundred thirty-four point fifty-six. In .NET if you try parsing in Turkish culture

double.Parse("12.34")

What do you think the output will be? Well, it is 1234 as the .NET parser completely ignores the thousands separator even if that wasn’t your intention. What about the situation in JavaScript? You are completely on your own. parseFloat is just using en-US culture and that’s fixed.

That’s not all. How many digits are there? 10 you say? Raymond Chen disagrees Well at least from a .NET standpoint Arabic digits are also considered as digits. In JavaScript, you are on your own again.

Currency

Well, the simple fact is in Turkish and many other languages the currency symbol is written after the numeric value not before as in 100$.

Percentage symbol

In Turkish, the percentage symbol comes before e.g %50

Other alphabets

Let’s see some peculiarities with other Alphabets. One might think “Z” is probably the last letter in Latin alphabets. Enter the nordic languages

Danish and Norwegian Alphabets: A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z Æ Ø Å

As you can see there are three letters coming after Z.

In the Icelandic alphabet, Z is obsoleted!!!

Ok, but at least we cans say Z is the last letter if we consider plain English letters. Unfortunately no. Here’s the Estonian alphabet:

A, B, D, E, F, G, H, I, J, K, L, M, N, O, P, R, S, Š, Z, Ž, T, U, V, Õ, Ä, Ö, Ü.

Some alphabets like Dutch has digraphs like “IJ” which is sometimes considered a single letter. Some fun facts taken from the wikipedia article:

-

In Dutch primary schools, ij used to be taught as being the 25th letter of the alphabet, and some primary school writing materials list ‘ij’ as the 25th letter of the alphabet.

-

When a word starting with IJ is capitalised, the entire digraph is capitalised: IJsselmeer, IJmuiden.[5]

-

On mechanical Dutch typewriters, there is a key that produces ‘ij’ (in a single letterspace, located directly to the right of the L). However, this is not the case on modern computer keyboards.

-

In word puzzles, ij often fills one square.

And here’s the Nigerian alphabet:

Upper case A B Ɓ C D Ɗ E Ǝ Ẹ F G

Lower case a b ɓ c d ɗ e ǝ ẹ f g

Upper case H I Ị J K Ƙ L M N O Ọ

Lower case h i ị j k ƙ l m n o ọ

Upper case P R S Ṣ T U Ụ V W Y Z

Lower case p r s ṣ t u ụ v w y z

Not only Nigerian alphabet has 3 E letters but they have an I with dot like Turkish but the dot is at the bottom.

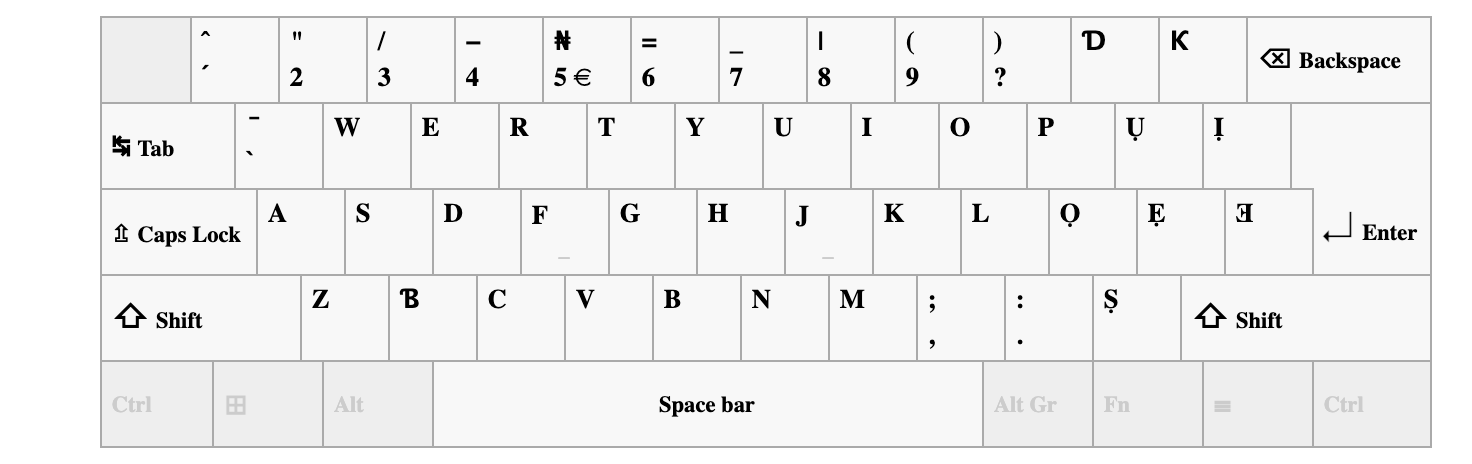

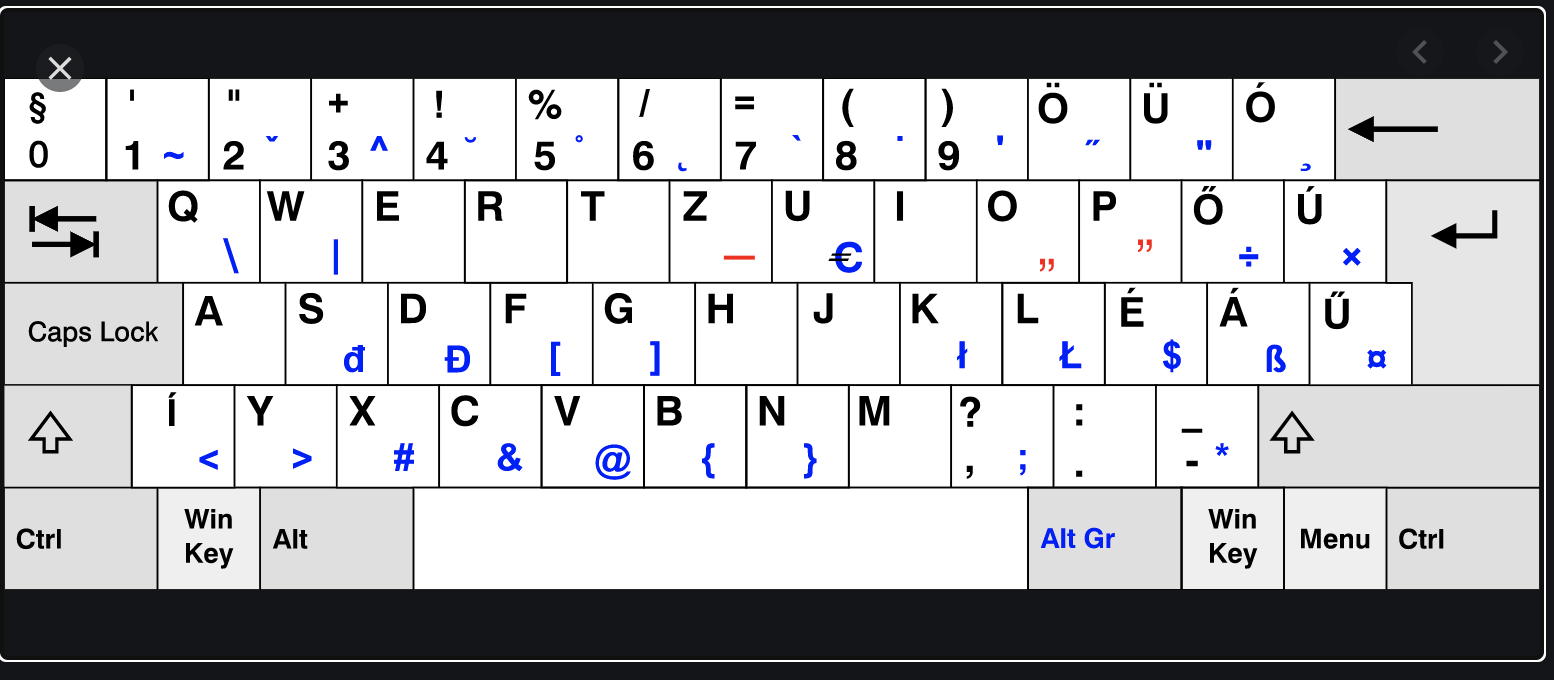

If you wonder things can go more interesting than this, ladies and gentleman, I present you Hungarian keyboard:

My non-elven eyes see there are 4 U’s and 4 O’s with different accents in the Hungarian keyboard most of them being at right hand side :)

Conclusion

Despite its widespread use, I have a feeling that JavaScript is not on par with backend languages like .NET when it comes to localization capabilities. What is the solution? You probably have to rely on third-party libraries. An alternative route might be to use Blazor which brings .NET Runtime into the browser. That way you can get the benefit of all the Globalization goodies of .NET but your app can still reside in the browser. Feel free to share your thoughts in the comments section.